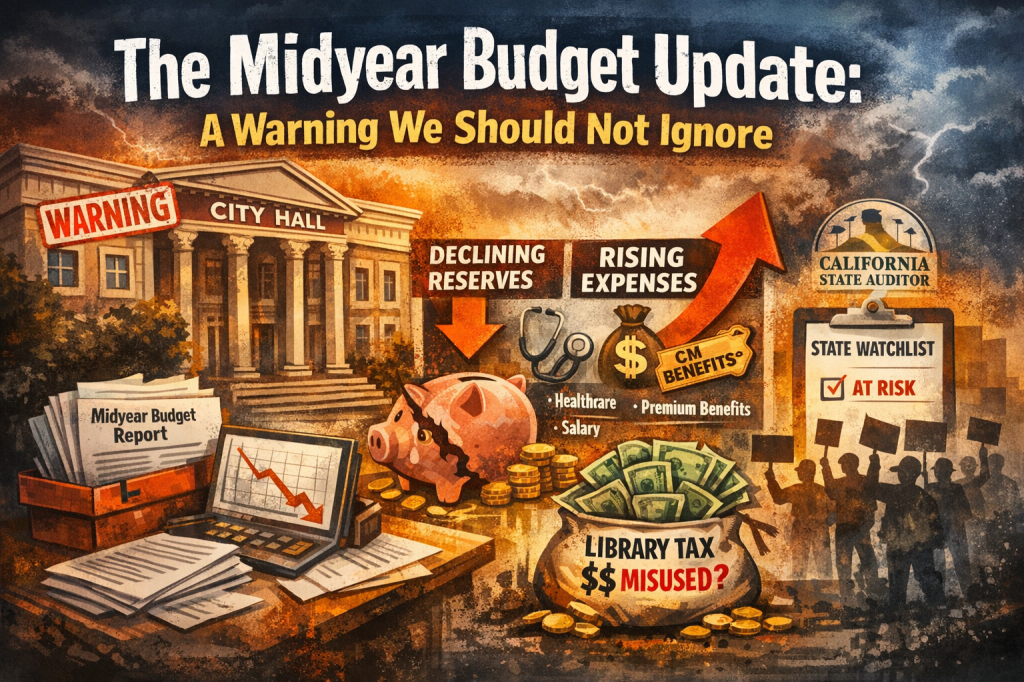

Pages 37–43 of yesterday’s City Council agenda packet, which contain the staff report for the Midyear Budget Update, should give every El Cerrito resident pause. Together with the accompanying budget presentation, they show a city that is increasingly relying on reserves to cover routine expenses, allowing costs to grow faster than revenues, and drifting toward structural imbalance. In FY 2025–26 alone, the City plans to use approximately $2.8 million from the General Fund balance, including more than $1.1 million in new withdrawals approved through mid-year amendments. During the Midyear Budget Update presentation, staff proposed several hundred thousand dollars in additional reserve-funded expenses, and the City Council approved those additional draws. This is not prudent fiscal management. It is a pattern of patching budget gaps with savings instead of fixing the underlying problem.

A key driver of the reserve reduction was the $1.045 million successor agency closeout payment. To be clear, the City had no real choice but to pay this obligation. It was legally required and unavoidable. However, staff bundled that mandatory payment together with several other discretionary and foreseeable items, making it extremely difficult for Council members to vote no on the overall reduction to reserves. When essential and nonessential items are packaged together, meaningful fiscal oversight is weakened. The result is an “all-or-nothing” vote that pressures elected officials to approve spending they might otherwise question.

What the public should not miss is that none of these items were sudden surprises. The successor agency obligation, rising labor costs, insurance increases, benefit expenses, and program needs were all known when this year’s budget was created. They were foreseeable. They were discussed in prior years. They were embedded in long-term forecasts. They should have been incorporated into the adopted budget last summer. Instead, they were deferred and reintroduced midyear as “adjustments,” creating the appearance of an emergency and limiting public scrutiny.

After these planned drawdowns, the City is projected to be only about $1.2 million above the minimum reserve levels recommended by the Government Finance Officers Association and required under the City’s own financial policies. That is an uncomfortably thin margin for a city facing rising labor, healthcare, insurance, and pension costs. It leaves El Cerrito with little room for error. One economic downturn, one major legal settlement, one infrastructure failure, or one recessionary year could push reserves below accepted professional standards. And let’s be honest, the city has planned cost overruns each year.

City staff acknowledged in both the written packet materials and the Midyear Budget Update presentation that expenses are rising faster than revenues. Non-personnel costs are increasing by more than 5% per year. Insurance costs jumped nearly seventeen percent in a single year. Personnel costs continue to rise due to healthcare, labor agreements, and pension obligations. At the same time, revenues are flattening. The City’s own long-term forecast shows that without meaningful spending changes, El Cerrito will begin running structural deficits starting in FY 2026–27. This is how financially stressed cities get into trouble. It happens slowly at first, then all at once.

Adding to this pressure is the City’s staffing structure. Compared to neighboring and comparable cities such as Albany, San Pablo, and Hercules, El Cerrito employs between one-and-a-half and two times as many staff. This level of staffing creates ongoing upward pressure on salaries, benefits, pensions, and healthcare costs. When a city carries significantly more personnel than its peers, every contract negotiation, benefit increase, and cost escalation is magnified. Overstaffing is not a neutral condition. It is a long-term budget driver that compounds fiscal stress year after year.

Yet this structural issue is rarely addressed openly. Instead, rising personnel costs are often framed as unavoidable. During the Midyear Budget Update presentation, Council members attempted to characterize many of these increases as “beyond our control.” Mayor Pro Tem Saltzman cited healthcare as an example. That argument is only half true. Healthcare is expensive everywhere, but benefit levels, premium sharing, staffing levels, and executive compensation are policy choices. They are negotiated by management, approved by Council, and embedded in labor and executive contracts. No one forced the City to adopt premium benefit packages. No one compelled Council to maintain staffing levels far above regional norms. These were decisions made by elected officials and senior leadership.

This matters because those decisions now limit the City’s ability to manage its finances responsibly. When leadership insulates itself from cost pressures, it erodes trust. It becomes much harder to go back to staff and ask for restraint when executives are protected from sacrifice and staffing levels remain untouched. It becomes difficult to convince residents that every dollar is being managed carefully when reserves are being drained to support an oversized workforce and premium benefits. Fiscal discipline cannot be something that applies only to frontline employees and taxpayers. It has to start at the top.

There are options available if Council is serious about long-term stability. The City could examine staffing levels relative to service demands. It could align workforce size with regional norms. It could require higher employee premium contributions. It could renegotiate executive benefit packages. It could establish firm cost-containment parameters in future labor agreements. It could align compensation growth with revenue growth. None of these steps require new taxes. They require leadership, political courage, and a willingness to make difficult choices before a crisis forces them.

The weakening of reserves is another warning sign highlighted in the packet materials and reinforced in the presentation. While current unassigned reserves remain near nineteen percent of expenditures, the City’s own projections show that they are now hovering just $1.2 million above minimum professional and policy standards. Once reserves drop below those thresholds, financial flexibility disappears. Emergency response becomes harder. Creditworthiness weakens. Outside oversight becomes more likely. This is precisely the trajectory that has placed many California cities on state fiscal watchlists in the past.

Even the City’s Financial Advisory Board has warned that expenses have increased over time and need to be controlled. When independent financial advisors raise concerns, the council should listen and take action. These are not political arguments. They are professional assessments based on audited data and long-term projections.

All of this has direct implications for the proposed library tax. Supporters argue that the funds will be protected and used only as promised. But when a government is under fiscal pressure, money becomes fungible. Restricted revenues are reinterpreted. Temporary “borrowing” becomes permanent. Promises become flexible. History shows that financially stressed cities struggle to honor earmarks when core operations are at risk.

El Cerrito has fallen into a familiar and dangerous cycle: rely on reserves, use one-time money, approve new spending, seek new taxes, and repeat. Structural problems remain untouched. Staffing levels remain misaligned. Accountability is deferred. Long-term reform is postponed. Each round makes the next one harder.

The story told by the agenda packet and the Midyear Budget Update presentation is not one of bad luck or unavoidable circumstances. It is the story of choices. Staff proposed reserve drawdowns. Council approved them. Known costs were deferred. Mandatory and discretionary items were bundled. Benefits were negotiated. Reserves were tapped. Reforms were delayed. Now residents are being asked to provide more money without meaningful structural change.

Before voters are asked to approve another permanent tax, City Hall needs a serious financial and governance overhaul. It needs enforceable cost controls, transparent budgeting, honest forecasting, right-sized staffing, shared sacrifice, and disciplined long-range planning. Without those reforms, new revenue will not solve El Cerrito’s problems. It will only delay the next crisis.