influenced by concerned citizens’ comments

Across Contra Costa County in 2026, fans of books and community space are facing temporary closures as multiple library branches undergo major renovations and infrastructure upgrades. These projects address long-deferred maintenance, including roofs, HVAC systems, electrical infrastructure, lighting, accessibility improvements, and air quality upgrades.

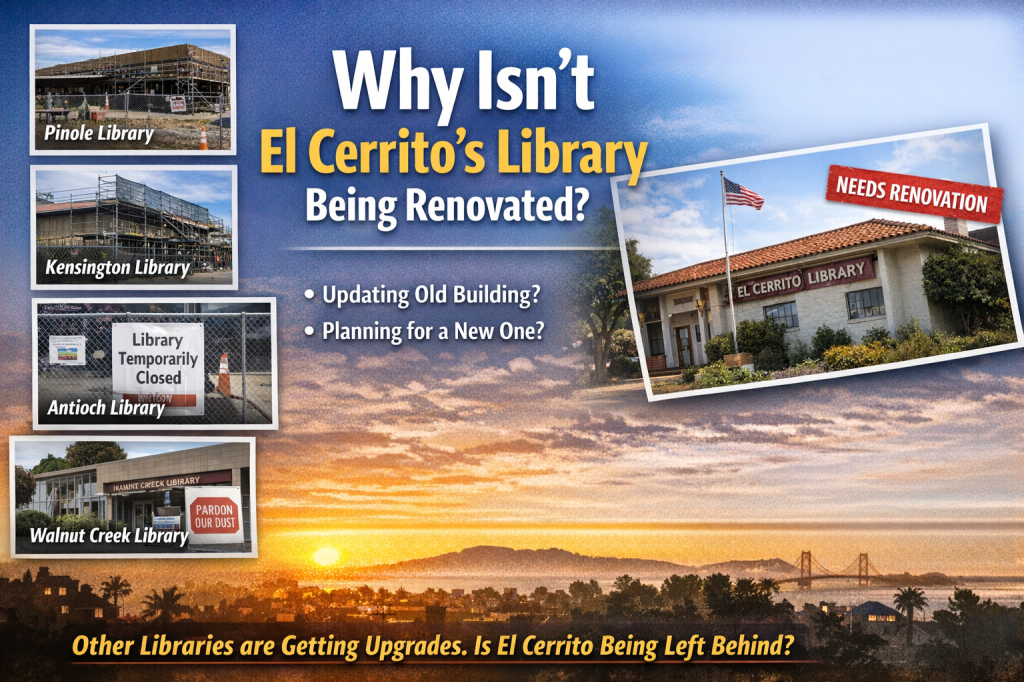

Libraries Currently Undergoing Major Renovations

According to Hoodline, four Contra Costa County libraries are scheduled for extended closures in 2026:

Pinole Library

Closing in March 2026 for approximately 11 months for a new roof, all-electric HVAC system, upgraded electrical and lighting systems, accessibility improvements, and air quality upgrades.

Kensington Library

Closing later in 2026 for at least a year to replace outdated HVAC, electrical, and lighting systems and complete ADA upgrades.

Antioch Library

Undergoing extended closure for electrical and lighting upgrades, ADA improvements, and parking lot and infrastructure repairs.

Ygnacio Valley Library (Walnut Creek)

Closing for months for roof work, electrical upgrades, and accessibility improvements.

Read the full article here:

https://hoodline.com/2026/02/contra-costa-book-desert-four-libraries-going-dark-for-months-of-fix-ups/

El Cerrito’s Library: Busy, Aging, and Still Waiting

Meanwhile, El Cerrito’s library continues to operate from its historic building at 6510 Stockton Avenue. Built in 1949 and expanded in 1960, the roughly 6,500-square-foot facility remains one of the busiest branches in West County.

Yet unlike Pinole, Kensington, Antioch, and Walnut Creek, El Cerrito’s library has not been scheduled for a major renovation.

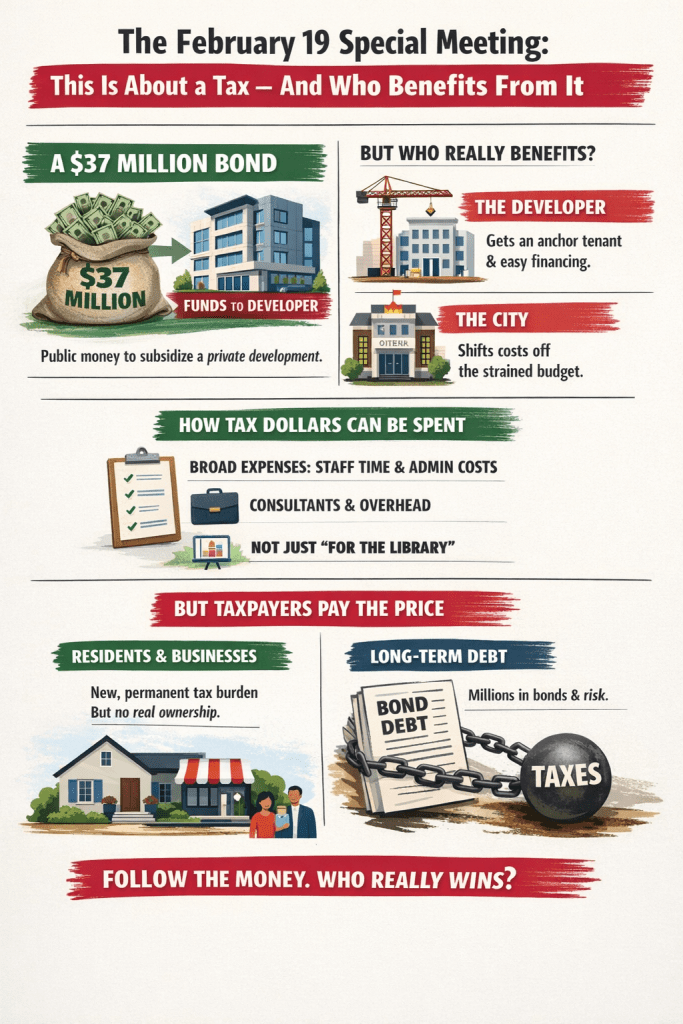

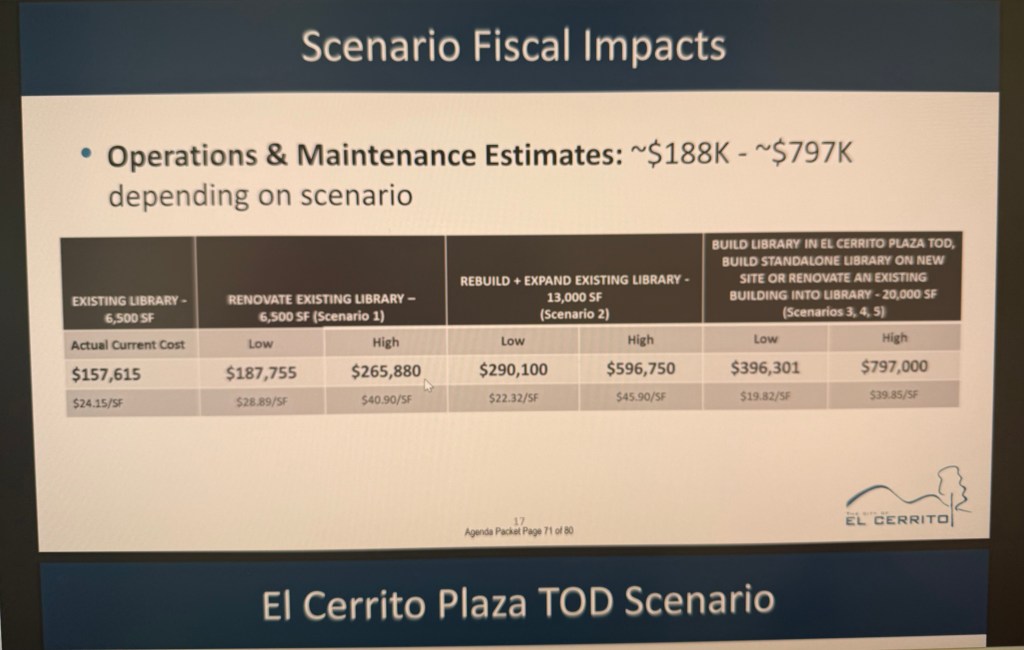

Instead, the City has focused for years on plans for a new replacement library, potentially tied to the El Cerrito Plaza Transit-Oriented Development project.

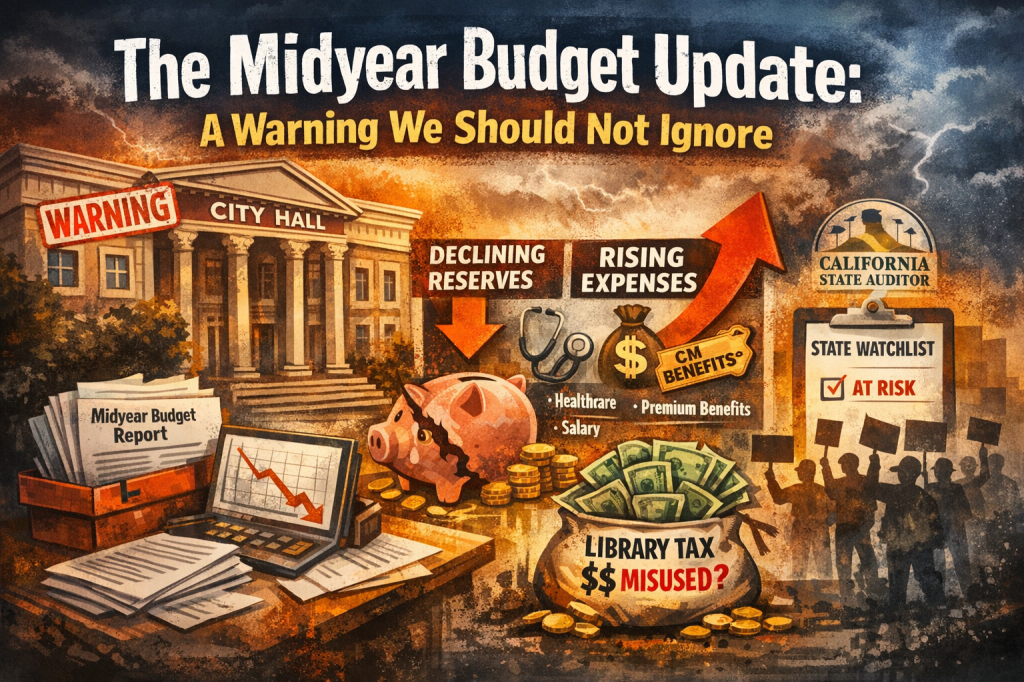

That proposed facility is estimated to cost at least $37 million to construct — and when financed through long-term borrowing, could cost more than $100 million in interest over time.

In other words, rather than investing in upgrading the existing building, El Cerrito residents are being asked to consider a project that could ultimately cost at least $100 million in total.

As of today, that project still lacks full funding and final approval.

Why Isn’t El Cerrito Renovating Its Library Now?

The contrast is striking.

Other Contra Costa communities are renovating existing buildings, fixing aging systems, extending the life of their facilities, and managing costs through targeted upgrades.

El Cerrito, by contrast, is being steered toward a high-cost, debt-financed replacement project — while the current building receives no major modernization.

That raises serious questions:

• Why hasn’t the City pursued a comprehensive renovation of the existing library?

• Would targeted upgrades cost far less than a new replacement?

• Is the focus on a large future project delaying practical improvements today?

• Are residents being fully informed about the long-term financial implications?

A renovated library can serve a community well for decades. Pinole, Kensington, Antioch, and Walnut Creek have recognized that.

El Cerrito deserves the same level of practical, cost-conscious stewardship.

A Choice About Priorities

Libraries are more than buildings. They are community anchors — places for learning, connection, and opportunity.

Right now, El Cerrito faces a choice:

Invest wisely in improving what we have, or commit residents to decades of debt for a replacement facility.

With other cities choosing renovation over massive borrowing, it is fair to ask:

Why isn’t El Cerrito seriously pursuing renovation first?